Every year, more than 380 million tons of plastic is produced around the world. A large portion of this plastic will end up in landfill, polluting our oceans and countryside, or be incinerated. In fact, with just 8.7% of plastic currently being recycled, chances are that well over 90% of the plastic we produce will end up being thrown away.

Plastic waste is already causing a number of serious environmental issues around the world. For example, it’s predicted that our oceans will have more plastic than fish by 2050, and microplastics are finding their way into our diet and even the air we breathe (resulting in the average person consuming around 5 grams of plastic per week). If the level of plastic waste in the environment continues to grow, this figure is only going to go up.

One possible solution to this global environmental issue is plastic eating bacteria. First discovered by Japanese scientists in 2016, the bacteria is one of the most exciting developments in our battle against plastic waste, opening new avenues for plastic recycling and providing hope that we can begin to tackle the single-use issue.

Source: theguardian.com

Plastic eating bacteria discovery

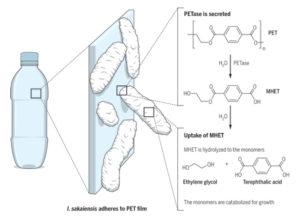

The discovery of plastic eating bacteria happened by accident. Scientists working in Japan collected sludge from outside a bottle factory in Osaka and found that it contained bacteria that had evolved to ‘eat’ plastic. Named Ideonella sakaiensis, the bacteria was able to decompose PET, a type of plastic used to make the majority of our drink bottles.

However, the bacteria worked fairly slowly, taking around six weeks to break down the plastic. This meant it wasn’t a particularly marketable option, especially when new products containing PET and other types of plastic are produced quickly and cheaply. The discovery of the bacteria was something of interest, rather than a solution to the plastic problem.

Through intense study and a series of breakthroughs, scientists have worked towards “evolving” the bacteria to work faster.

Making plastic eating bacteria work faster

Following the publication of the Japanese plastic eating bacteria article, scientists across the world began developing new types of plastic eating bacteria and enzymes. They looked at how plastic eating bacteria works and discovered how to make it more efficient.

Source: earth.org

In 2018, British scientists used the research to modify the bacteria to make it work faster, offering hope of a realistic alternative to the original slow-working discovery. This mutant version broke down plastic around 20% quicker than the naturally occurring bacteria, and it was also effective on harder plastics, increasing the number of potential applications.

Further developments followed, with scientists finding ways to connect two bacteria to create a strain that works even faster. This was a breakthrough as it opened up the possibility of combining bacteria that broke down different substances too, essentially creating a “bacteria package” that could work on multiple types of plastics and other materials.

In theory, these packages could allow scientists to create a super-enzyme that works to decompose a mix of materials including plastic, polyester, cotton, and others. This is important because when base materials are combined in products such as clothing they become unrecyclable, but by creating bacteria that breaks them down into their separate components, it could make these materials recyclable and reusable once again.

In 2020, French company Corbios released a modified enzyme that could degrade 90% of PET bottles within just 10 hours. The only downside of the enzyme was that it required temperatures of around 70˚C to be effective. Building on this knowledge, a team of British scientists developed an enzyme that’s able to work quickly and operate effectively at room temperature. This makes bacteria that eat plastic a potentially viable alternative to other plastic recycling processes.

Problems with plastic eating bacteria

The idea of a bacteria that can eat plastic is very appealing to those concerned with the exponential growth of plastic waste in our oceans and landfills. The process has its problems, and several plastic eating bacteria research papers point out potential issues with using the process at large scale.

For example, some toxins are released as plastic eating bacteria by-products. These have the potential to harm the environment more than the plastic waste itself, and since they are entirely lab-created, they are untested in the environment. Secondly, the decomposed plastic monomers need to be separated from the other substances in the mix for them to be recoverable. This adds to the time and cost involved in breaking down the complex products that we produce, making the process less commercially viable in the long run.

How could plastic eating bacteria actually work?

It’s cheaper and faster to produce new plastic than it is to use plastic or microplastic eating bacteria to break down used bottles and products. The good news is there are major plastic-using companies, like L’Oréal, Nestlé Waters, PepsiCo, Suntory Beverage, and Food Europe who are collaborating with researchers to gain more information about plastic eating bacteria. In the future, it’s possible that plastic eating enzymes could play an important part in plastic recycling and help us to undo some of the damage that’s been done to the environment.

In the meantime, it’s important that plastic waste is properly diverted and recycled. Dealing with bottles, packaging, and other products responsibly helps minimize the amount of waste that ends up in landfill and our oceans. For more information on how your business can optimize responsible waste management processes through on-demand and recurring collections, contact one of our TRUE Advisors today.